Treating “Activity-itis” (Assessing &

Adding Value and Quality to Activities)

Class time is precious and limited. With so many standards to cover and stakes being so high, it is imperative that everything we put in front of our students be standards-based, purposeful, and designed to drive and assess student growth. Over the years, I’ve reflected on some activities that I’ve done with students and realized that maybe just maybe 🙂 some of them were “fluff” in terms of standards. Don’t get me wrong. Some assignments are fun, make personal connections, or meet other goals. However, some are just not designed to do much other than keep students busy or produce something cute or trendy for a social media post. In the past, I have certainly been afflicted with “activity-itis.” This post explains how to assess and add value and quality of your classroom assignments and activities.

THE SYMPTOMS OF ACTIVITY-ITIS:

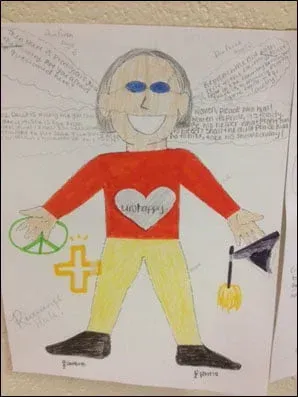

The students have no idea why they are doing the activity. You could probably argue that there will always be students who are clueless in a sense that they aren’t trying. In this case, the problem goes much deeper. There are times when I dive right into a lesson or activity and just don’t tell my students why we are doing it or what it connects to. If I just forget to tell them, that’s one thing, but if I can’t answer the questions “Why are we doing this?” or “What are they learning from doing this?” then why are we doing it? Why are we building a model of a fire-proof house with our 451 unit? Guilty. Why are we drawing a picture of our favorite character in The Lord of the Flies? Guilty again. Instead, let’s trace the symbol of fire throughout the novel and analyze how it changes. Let’s read an informational text about how fire works and make literal and symbolic connections. If we want students to get to know characters, let’s have them create a body biography with text-based descriptions. Just making some tiny, purpose-driven adjustments can spark huge changes in students’ growth and understanding.

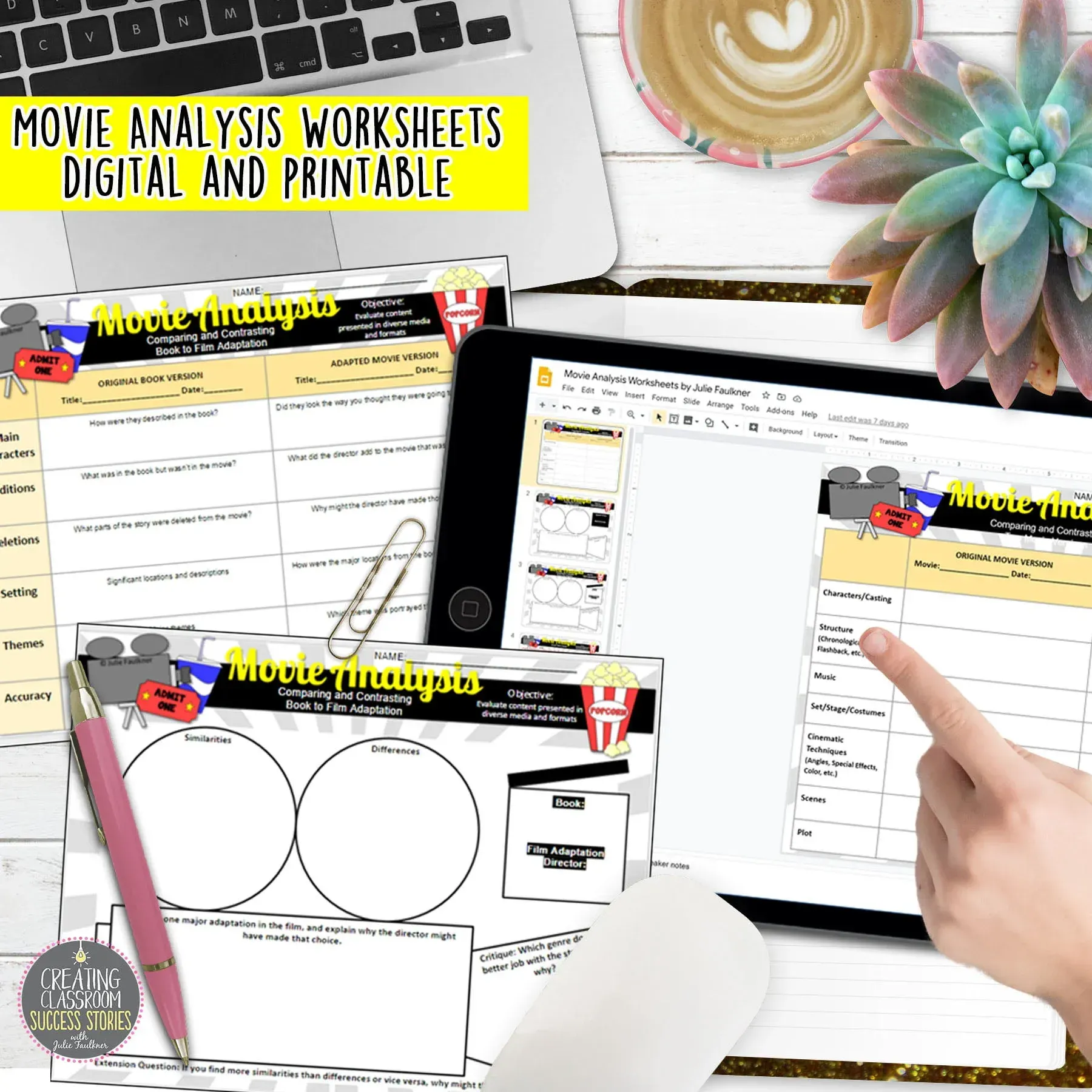

The students are busy, but there’s no challenge. I suppose this could happen for a couple of reasons, but like I said before, class time is precious and limited. Coloring, watching movies, listening to a podcast — just for the heck of doing it or because everyone else on social media is doing it. I actually use and sell resource for these types of activities; however, there is always something students are doing that is skills based. Yes, coloring and movies make excellent brain breaks and sub plans, but even then, I just can’t get behind vacuous time-fillers. If students are coloring in my class, they will be editing sentences in order to color by number. If they are watching a movie, they are analyzing structure and style. More on using movies effectively in this post. If we are listening to a podcast, we are making connections, analyzing plot, or more — we aren’t just doodling. There is always something that can be done to up the ante with any assignment.

The activity steps too far out of its subject, isn’t grounded in standards, or isn’t connected to any prior or future learning. I think this one creeps up a lot in English class because we do so much with texts that we feel we need to introduce. When I first started teaching The Crucible, I felt I had to tell students everything they needed to know about Puritans before we started the unit. Then I had to spend another day or so talking about the 1950s. Then, yet another day was spent covering the elements of drama. A week or more had passed and we hadn’t even started reading the text; and my kids were bored and over it. Eventually, I stepped back and asked myself, what I am I doing wrong? I love this play so much, but the kids hate it. Then, I realized: it wasn’t the play they hated, it was the presentation. Wow. So, how did I fix it? I asked myself one question: Why am I teaching this play? The answer? It wasn’t so they could learn the history of the Puritans. It wasn’t so they could understand the 1950s. It is so we could analyze a true hallmark in the canon of American literature — for the literature, to see how an author can craft a story that conveys both so creatively and expertly that we really don’t need much else than the text itself. In that regard, the only intro material I kept was one short informational text article about McCarthy and a quick vocabulary lesson on allegory. Then, we just dig in. I let the text do the talking. I developed questions, prompts, close reading exercises, and activities that drove students further and further into the text. The result? Students who enjoyed the play more than ever before, and students who were mastering standards. More ideas on how to start a unit here.

The activity lack true engagement and/or collaboration. Students aren’t talking at all or aren’t talking about the actual task. How many times have you overheard students saying “What’s for lunch?” or “I have to work this afternoon” during an activity? Sure, students get off task with even the best designed activity. However, a key symptom of activity-itis is students who are off-task. If I have students in groups, what I really want them to be able to do is collaboration, bounce ideas off each, and share out. I want them to even learn to hear different ideas and defend their own answers. I love to have students think first, and talk second, so they have something prepared when they join the group. Task cards are hugely helpful with getting kids thinking and giving them direction. More ideas on using task cards in the classroom here.

There is no assessment, the assessment isn’t a challenge, or there is a discrepancy between the assessment and the activity. If at the end of the day, I’ve done a lesson and can’t measure if the students really “got it,” then I’m pretty much in panic mode. For me, it can be as simple as asking them. Other times, I’ll have a worksheet they have to complete. Other people like to do the ticket out the door. Another issue here is when the assessment only asks the students to regurgitate what they’ve already been told in class and there’s no application to show their learning. It’s very important that students can apply the skills they’ve be taught, so you can see if it stuck. I almost never give a final exam on the story we’ve read in class where students recall details of the story. That doesn’t assess their hopefully newly acquired knowledge of plot, characterization, or symbolism. Rather, they will write about it, do another project with it, or read a shorter text and answer questions that test those skills. Whatever you choose, again, it needs to be purpose-driven, and truly measurable.

THE CURE

- Design, discuss, and post essential questions to drive planning and measure learning. For more tips on creating essential questions and creating standards-based lessons and activities, take a look at my CC standards aligned depth of knowledge chart where I’ve aligned every ELA standard 9-12. More on using essential questions here.

2. Student self-reflection. This isn’t always easy, but with particularly reluctant groups, I have success with my weekly reflection task cards that come in my student-directed data pack. More on data collection here.

3. Think about the end goal when planning. In other words, plan backwards. In order to help myself remember this important piece, in every one of the teacher planners that I design, I have a reflection page at the end of the month. It reminds me to pause and reflect on what we accomplished and need to work more on. More on planning backwards in this post.

4. Assessment and measurement that are consistent and align with the skills.

5. Make connections to prior and future learning. This can be done effectively if you work inside of units where a big picture is evident. A KWL chart activator is perfect tool for making connections. I also love to do the 3-2-1 strategy.

https://www.instagram.com/tv/CTxJ6d5gWnK/

Yes, there are crazy-day schedules, half days, sub days, or sick days, or any number of random odd days occasionally when we need a quick low-stakes, no prep activity, but even those days need to be utilized to matter. Ultimately, I now evaluate each lesson and activity I plan for its standards-based value.

Love this content?

Sign up for my email newsletter with more tips, ideas, success stories, and freebies!