How to Select & Use Paired

Texts for Teaching Reading

In my previous post on the Benefits of Using Paired Texts to Teach Reading, I discuss the advantages of this brain-based teaching method. It’s no secret that offering ways for students to making connections — text to text, text to self, and text to world — is an opportunity to exercise higher order thinking skills. Teaching shouldn’t happen in a vacuum, even though sometimes it does as we stress to move units along the conveyor belt, more acceptably known as pacing guides. Often and unfortunately, we teach one skill and move quickly onto the next. Confession: I don’t teach that way. Everything must build and connect from unit to unit, text to text, and skill to skill. That’s why paring texts is so important, and in this final post in the series, I want to share the practical, actionable ways that I select and use paired texts for teaching reading.

1. SELECT TEXTS THAT HAVE RELATED THEMES

Most standards now require something to the effect of, “Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take.” In fact, in the CCSS, theme is mentioned in the second anchor standard for reading: “Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development.” There is no denying that teaching theme is an important part of teaching reading. Over the years, I’ve noticed that when teaching theme with one text, students do slowly grasp the concept. But, when I add that next layer of a paired text and ask them to consider what universal message the texts share, that’s when the light bulbs ding on. Since texts can have multiple themes, you’ll want to pick the one that is most overarching and/or universal — And the one that you really want students to focus on for the duration of the unit and possibly the one they will focus on for their final culminating task.

In my Lord of the Flies unit, for example, we read Paul Laurence Dunbar’s “We Wear the Mask,” and I ask students to synthesis between the novel and play how the concept of hiding behind a mask emerges as a theme.

2. SELECT PAIRED TEXTS THAT PROVIDE AUTHENTIC AND RELEVANT BACKGROUND INFORMATION

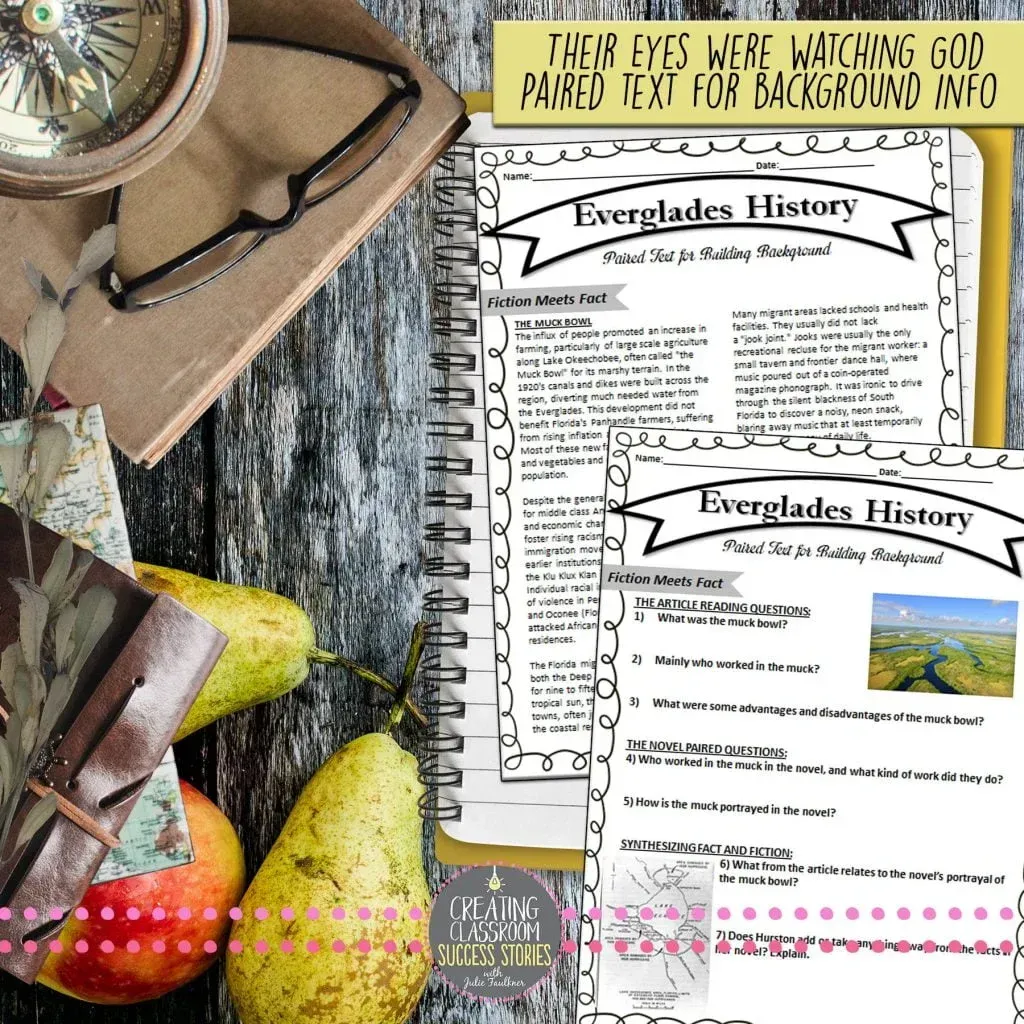

When I start a unit that requires a bit of background information for students to fully understand the setting, conflict, etc., I like to provide that information. Rather than “read” a Power Point lecture to them, I bring in an article or excerpt from a history book that provides the content they need — only they are doing the work extracting that information instead of me just reading it to them. Sometimes, I can’t always find one text that does the job, so I’ll write up a faux article using several sources. If you have accelerated students, that would be an excellent task for them to do.

For example, when we read Their Eyes Were Watching God, I want students to understand the historical context of the Muck Bowl, so they can fully appreciate the conflict Tea Cake and Janie experience. Here I used several sources to craft this faux textbook excerpt. On the worksheet, I ask students questions about the historical content itself, and then they apply that information to the novel.

Fire is such an important element in the novel Fahrenheit 451, so I don’t want students to miss its value as a literary element; thus, that understanding is further enhanced by gaining scientific knowledge about how fire works. From the first page, we track fire as a motif throughout the novel, and then near the end, I bring in a scientific article that explains how fire works. By then, they have a full picture and lots of textual evidence to make connections.

3. SELECT PAIRED TEXTS THAT REPRESENT ANOTHER POINT OF VIEW OR VOICE

One of the benefits I mentioned the first post in this series of using paired texts for teaching reading was that pairing texts allows for diversity. If your curriculum calls for authors who are too close in ethnicity, gender, etc., pairing a text can open the door for more diversity. It also allows students to see themselves and see topics from different points of view.

In my Trifles unit, I pause to read Paul Laurence Dunbar’s “Sympathy.” Not only does this poem connect based on theme, but it relates the experience of being trapped from a Black man’s point of view — totally different from the white female author’s voice in the story. We can discuss how anyone can feel trapped and for so many different reasons. This type of paring really does open students’ eyes and free up higher levels of learning.

4. SELECT TEXTS WITH INTERTEXTUALITY

Intertextuality might be an unfamiliar word, but it is a very common practice in the literary world. There is certainly “nothing new under the sun” (Ecclesiastes 1:9). The term was first coined by the Bulgarian-French philosopher and literary critic, Julia Kristeva in 1966. According to Kristeva, when readers read a new text, they are always influenced by other texts, which they have read earlier. When a writer borrows from other texts while writing his/her own, he/she attaches layers of meanings to his/her work as well. When that work is read under the light of the others, it gives it a new meaning and interpretation.

Thus, intertextuality is the relationship between texts, especially literary ones. In fact, it can be argued that every text is a product of intertextuality. It’s that feeling of Deja vu: You’ve read this somewhere before. Well, you likely have. Essentially, intertextuality is the retelling of an old story or the rewriting of popular stories in a different set of contexts. It is not a remake, though, as in the instance of one of the Hunger Games books being made into a movie or the various remaking of every Disney movie ever from cartoon people to real people. It’s also not allusions to other texts, either, as in the way Collins infuses elements from Fahrenheit 451 or Greek Mythology in The Hunger Games. However, the entire concept and plot of The Hunger Games is a modern retelling of Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery — that’s intertextuality. Another example of intertextuality is between Miller’s The Crucible and Jodi Picoult’s Salem Falls: modern setting, same plot, conflict, and themes. More examples include:

- Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby retold in Sparks’s Dear John

- Shaw’s Pygmalion created into My Fair Lady and again into the movie Miss Congeniality

- Shakespeare’s Hamlet rewritten into The Lion King

- Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet retold in the Twilight Series

- Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus

- Anderson’s The Snow Queen refashioned into the beloved Frozen

Because you must experience both texts from beginning to end to fully grasp and evaluate the intertextuality, it can take some planning in how to pair these types of texts in the classroom. If it’s a movie remake, that’s the perfect way to close the unit. Ask students to make a Venn diagram to compare/contrast the differences or have them create a mirrored set of plot charts. I’ve also shared the modern versions as part of my First Chapter Friday readings and had students check out the paired text. You could also do it for out of class reading for advanced students or as summer reading, as well.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B9FhhlZA13t/

5. SELECT PAIRED TEXTS TO ADVANCE A CHARACTER STUDY

The characters are why we read: we fall in love with them, we love to hate them, we want them to survive, we share in their triumphs, we feel their joy and sadness. Selecting paired texts to teach characterization is an excellent way to enrich the reading experience. You can have students compare how the two main characters handled situations different and why. You can have students study the way the author chose to develop them: point of view, descriptions, voice, and more. Sometimes you can compare characters in different texts from the same author or characters from two entirely different texts. It depends on your purpose.

In my A Rose for Emily unit, I bring in a nonfiction article about a woman who couldn’t let go of her dead family member either and a poem from Emily Dickinson wherein the speaker wishes to be alone. Here, I’m making the story relevant and extending our study on characterization: What motives do they share for this behavior and why? Why do they choose isolation? This technique opens up a whole new world of analysis.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CDCSlVIneld/

It’s important to conduct a close reading of each text individually first before comparing texts or integrating the information from the layer. Teach the process; teach students how to compare/contrast and explain why. We want students to be successful and really experience the higher order thinking that studying paired texts can offer, so we have to be prepared to teach those skills explicitly first. This means it could actually take a week or more to walk students through close reading and annotating each text individually, especially if it is going to be part of an in-class unit. Check out my Textual Analysis Worksheets if you don’t teach these texts I shared. You’ll find tools for comparing your favorite text pairs.

Aside from all the standards that are covered when you begin adding layers and pairing texts to teach reading, imagine the doors that you’ll be opening up for students — doors (in the form of novels, articles, movies, poems, etc.) that they may have never “walked through” before. As English teachers we love reading and know it’s value; pairing texts to teach reading is just a sneaky way to share that love ♥ Speaking of sharing — please drop your favorite paired texts for teaching reading in the comments below!

Love this content?

Sign up for my email newsletter with more tips, ideas, success stories, and freebies!