A Formula for Teaching Writing

with Success, Series #1 Planning

A couple of years ago I did a series on my formula for classroom success. It entailed topics like classroom management, planning, organization, etc. You can check all those topics out here. In those years since, I have been developing a resource and a series that defines my formula for a different topic: writing instruction. I get asked all the time for help and tips for how to teach writing, and I never really knew how to answer my colleagues who asked me to pinpoint what I did. I’ve seen success with my students’ writing in my classroom over time, and I’ve had successful writing scores on standards tests. But what really makes good writing instruction? Where do you even begin? How do inspire students to write… to buy in? So in the past year or so I’ve made a conscious effort to consider my practices and process when it came to writing. What I realized was pretty astounding and simple at the same time. I hope that by the end of this series (over the next several weeks) that you’ll feel empowered and recharged and ready to tackle all those writing standards.

I’m starting the series with the planning piece because I think that’s like the atom in science – it’s the basic fundamental piece that must be studied and addressed and understood before moving on. I like to plan, so for me that seems natural and naturally exciting. Others might like to dive in head first and just take off and see where it goes. However, the problem with that approach can lead to derailment along the way in the form of running out of time for critical pieces of the process. No plan is ever perfect; we do certainly have to be fluid in the process, but ultimately knowing where you are headed before you take off is the best course of action. If you are ready to join me on the journey to successful writing instruction, here are the five pieces I start with each semester when I start to make my curriculum map.

1.

So, what did I realize? I won’t keep you waiting until the end of the post for the answer to this one. I can’t, really. It’s just too big of a deal. So, here goes: Writing isn’t just something I throw in every now and then or when I’m mandated by the central office. It isn’t an afterthought when I’ve finished my “big unit” or have a few extra days somehow. It IS the big unit: three of them in fact. They are also known as narrative, argumentative, and explanatory. With that said, planning begins with the end in mind. Shape your units to the modes with essential questions and outcomes upfront. For me that pans out to a narrative unit, followed by an argumentative unit, and ending with an explanatory unit. (I do a research project in correlation with my book club study. Read more about that here.) Here’s a snapshot of the pacing guide I use with my juniors. A similar (and editable) one is included in my writing curriculum.

I choose narrative first because it is the least restrictive mode, and it allows students to step into writing without all the formality. They can just use their imaginations and let it flow. I can cover some writing fundamentals that carry over into the other units like writing strong hooks, word choice, and even touching lightly on textual evidence without them feeling so stressed about getting the content right. What I mean by that is with narrative writing, they aren’t trying to analyze a scientific text or refute counterclaims with a certain precision of logic. Those restricting elements are off the table, and for the most part, students can just write. It builds confidence. Also, as part of the pacing guide, I develop a list of words that are critical for each unit. I pass those on to students in the form of a vocabulary list. We go over that list before we even start each unit, and I quiz them over the list, too. The vocabulary of a mode is critical. We can’t have conversations about writing — narratives, hooks, counterclaims, thesis statements, or citations — if those words are foreign to students. Teaching the writing vocabulary up front builds students’ writing schema and confidence.

2.

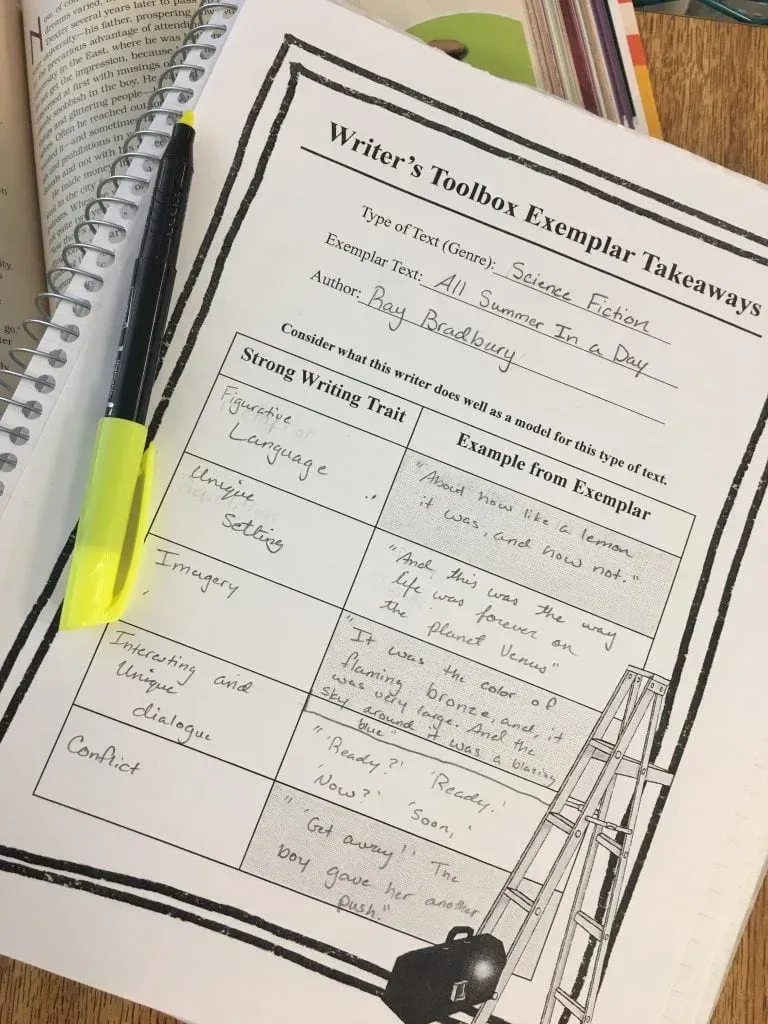

The next piece that I look at when planning my writing units (aka year) is the anchor texts that will ground each unit. Since no English curriculum is complete without literature and nonfiction — and all curriculum guidelines and standards include them — they play a critical role. I don’t want anything to feel random, and I don’t really have time for that either because I’m on a block schedule and every minute counts. I select one anchor text per unit. These texts are from my department’s reading guides, textbook, standards, etc. I pick grade-appropriate selections that will make the most impact – ones we can dig into for days and even pair smaller texts with when time allows. Speaking specifically about my junior class, for the narrative unit, in the past I’ve read a variety of short stories: “All Summer in a Day,” “To Build a Fire,” “The Pedestrian,” “A Rose for Emily,” and so on. It just depends on what group I have in front of me, how much time, etc. For my argumentative unit, I pick a strong argumentative professional model, usually from the canon. We most often read Patrick Henry’s “Speech in the Virginia Convention.” The explanatory mode is so much wider open than any other mode. I usually pick a text that needs to be covered for its literary value and is dense enough to develop many different topics and material for evidence in essays. Usually, for my juniors, that’s The Crucible. Since I’m covering these texts as anchor texts and I don’t usually cover any other texts in class outside of these units (and my book club text), they must be solid. Quality over quantity will win out every time in my book, so I must choose carefully. Plus, since I am using these texts not only for writing anchors and models, but also to cover many reading standards as well, these texts are the units inside the units, and I have to plan to give myself space in the calendar to cover them adequately enough. That can be 1-2 weeks, more or less. To close the study of the professional anchor text in the given mode, we do an activity that I call the “Author’s Toolbox.” Here we change hats. We take off our “reader’s hat” and put on our “writer’s hat” to see what tools from the professional writer’s toolbox we can “steal” for our own.

3.

A planner’s job is never over it seems, but you can’t stop the clock until you’ve also thought about what prompts your students will write. Since the units are anchored with texts, you may choose to have students write in response to those texts. I think that works very well in some cases. I have students change the ending or resolve the suspense or write from a different point of view in the narrative unit in response to the short story. In the explanatory mode, we explore the causes and effects of mass hysteria in The Crucible. Prompts must be chosen in a way that requires students to respond to a text, not just repeat what was covered in class. Often, with my argumentative mode, I’ll pull in two or three new short texts entirely and have students perform their skills cold. Plus, I like to mix up my prompts in different semesters to prevent plagiarism and keep up-to-date. It just depends on your scenario, time allotment, and objectives. I did have a curriculum adviser once remind me in planning a prompt that there is a difference in prompts designed for writing assignments and prompts designed for writing assessments. Long, dense prompts might work for the culminating writing assignment of your unit but not for a writing assessment. We want to set students up to perform their skills successfully and purposefully, not set them up to fail.

4.

Possibly the easiest to plan for is the time students will need to compose the assignment. I do give my students time in class and out of class to write. I like to see them writing, so I can observe their process. This also helps if you wonder if they are really doing it themselves or not. As part of this time, too, I schedule intermittent deadlines. For my argumentative unit, for example, the first deadline comes soon after the task has been released: the thesis statement check. I also schedule time for conferencing with students while others are composing. This usually takes one or two days, and I’ve recently started doing this via Google Classroom. Students submit to me, and I can leave suggestions to them in real time. In my timeline, students are usually writing a 500-750 word essay over the span of three-four class periods and one weekend. It’s also important to note here, too, that you do need to go ahead and think about charting off time for students to reflect and revise after the scores have been returned.

5.

Last, and maybe the most overlooked is planning some time for you — not to get a manicure, at least not yet 🙂 — but to grade all those essays coming in. IF you can grade during school hours, that’s what I would suggest. I know it’s not always possible, but if you can plan to show a movie that coincides with your unit or one that might replace a novel you won’t get to cover, that’s an easy way to get yourself some time at work to grade essays. There are so many ways to use movies meaningfully in class, so students are learning and standards are being covered. Another idea might be to pull in a project for students to complete or maybe an informational hot topics text lesson. You may can’t give yourself but a day or two, but something will help with that load.

It may seem odd that I would start a series on successful writing instruction with a post that had really almost nothing to do with the actual instruction. However, that’s coming, but this content really is the secret. Good writing instruction is based on a good plan. Not the kind of plan that says, “Oh, I’m planning on doing it”… but never really getting around to it! But rather the kind of plan that gets you going in the “write” direction for the year. Every piece of what I do builds on the other and connects and flows. Without a plan, that wouldn’t be possible. I read a quote once that said, “Don’t tell people your plans. Show them your results.” I disagree with that. I think you should show people — your students — your plan, and that is what will get the results.

Here’s a quick video of my explanation of planning and pacing an English unit here.

Follow to Post #2 and Post #3 here!

Be sure to get this blog straight to your email, so you won’t miss the next post in this series: The Writer’s Notebook. (Find the big SUBSCRIBE TO NEWSLETTERS in "Stay Connected" Tab!)

Love this content?

Sign up for my email newsletter with more tips, ideas, success stories, and freebies!