Teaching Arthur Miller's The Crucible

Cover it All and Engage Your Students

From the history to the hysteria, the fears to the fury, and the lies to the love story, it is understandable why

The Crucible is still a staple in many high school English classrooms. There are so many layers crafted in the lines of Arthur Miller’s magnum opus, but that can be a blessing and a “curse.” Such a rich plot line can be a literature teacher’s dream come true; however, it can also raise two concerns: 1) how much is too much to cover and 2) what if I miss something important? We don’t want to “burn” the students with boring information when teaching

The Crucible, but we do want to make sure they have the full picture to best understand and enjoy Miller’s creation. In this blog post, I’ll be sharing how I set the stage to engage my students and how to teach Arthur Miller’s

The Crucible.

TEACHABLE MOMENT #1) ALLEGORY > MCCARTHYISM

What It Is: Arthur Miller had very specific reasons for writing The Crucible in the 1950s, and one of those reasons was to expose the issues circling in the government at the time period. These issues were known as the Red Scare, and the hysteria of this time period was spurred in part by a man named Joseph McCarthy. His own political agenda fueled by greed and vengeance paired with the public’s genuine fear of a Communist takeover was the perfect storm. Therefore, it is important for students to understand the historical context before they start reading the play. I tell students that fighters fight with their fists, but writers fight with their words. Miller wanted to reveal the truth behind the Red Scare by using his platform and position in Hollywood.

How I Teach It: This is actually where I start my unit. (Read here for more ways to start a literature unit.) I briefly define allegory, a story with a double/symbolic meaning, and then since none of my students lived through the 1950s 😉, I take a day or class period to provide an overview of the Red Scare. Typically, students read an article with a set of succinct questions that I’ve written to point them directly to the key issues of that time period: McCarthy’s motivation, HUAC, fear of communism, victims of accusations, etc. I never spend days at a time teaching historical background information because my purpose in teaching the text isn’t historically driven but is important to cover this historical information so students will be able to recognize the allegorical layer of the text once they start reading. (Hear more on my thoughts of keeping background info minimal.) Opening the unit with a quick overview of the historical context and how that makes the play an allegory give students a deeper understanding and also lays the groundwork for the play’s important themes that will emerge later in the unit, but it doesn’t bore them. You can grab the article and questions that I use in my The Crucible Complete Literature Guide.

TEACHABLE MOMENT #2) PURITAN CULTURE AND THE SALEM WITCH TRIALS

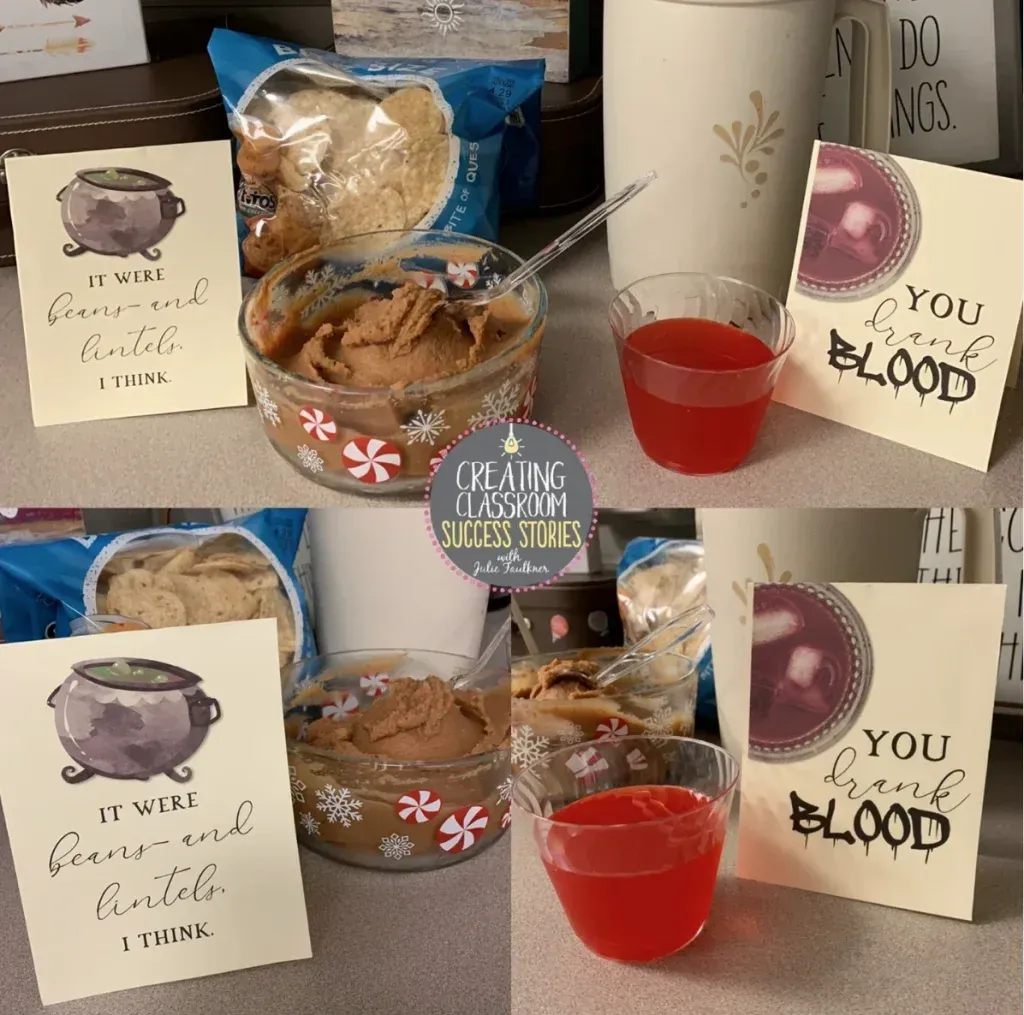

What It Is: Once students know that the play was written in a way to “throw shade” or “call out” issues of the time period in which it was written, learning about Miller’s character choices makes more sense. While the play is fiction, it is based on facts – the facts of the Salem Witch Trials that occurred in 1692 where 25 people fell victim to the hysteria. Miller couldn’t use the villains of the ’50s as his characters, so he turned back the pages in history to centuries before, when unfortunately a similar hysteria had taken place. The Puritans, a devoutly religious group who came to the “New World” on a divine mission, set out to eliminate any signs of evil influence or deviant behavior from their small town in hopes that their own path to heaven wouldn’t be destroyed. Miller took these facts and bent them to fit the plot of his play.

How I Teach It: Because the main characters are the Puritans, many teachers choose to take several days to explain their beliefs and lifestyles. I’ve done that, too, but I realized very quickly that too much front-loading can take away from the “magic” of the text and also eliminates the possibility of students drawing their own conclusions about the Puritans from right inside the text using Miller’s crafty characterization, dialogue, and conflict. In lieu of long presentations and pages of notes about Calvinism, Puritan class and government structure, and even Salem, when I’m teaching The Crucible, I elect to quickly overview this topic with a set of task cards that I set up in stations for students to rotate through if I have time. If time is short, I’ll use a brief video with the same information. This puts accurate information in my students’ schema, so once we start reading, they can make their own inferences – but inferences based on fact (standard covered!)

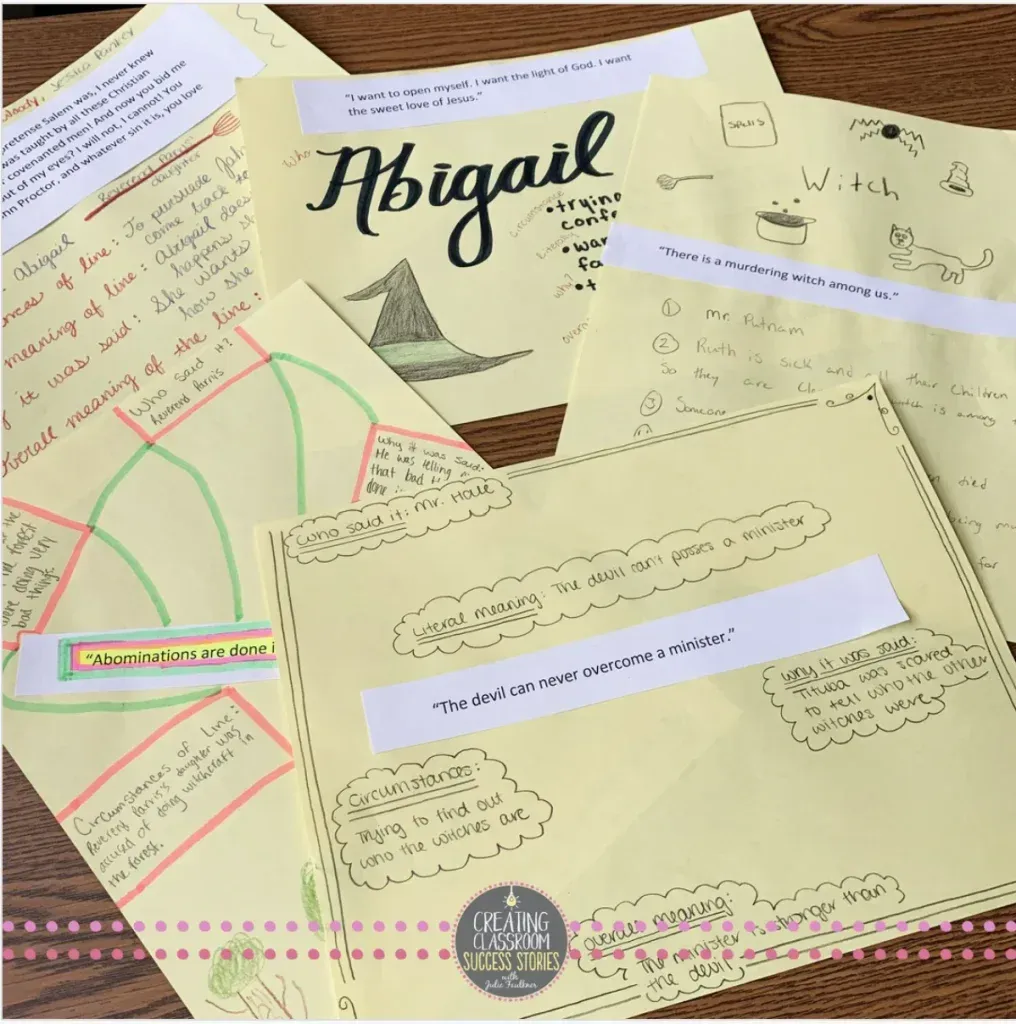

TEACHABLE MOMENT #3) FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE IN THE CRUCIBLE

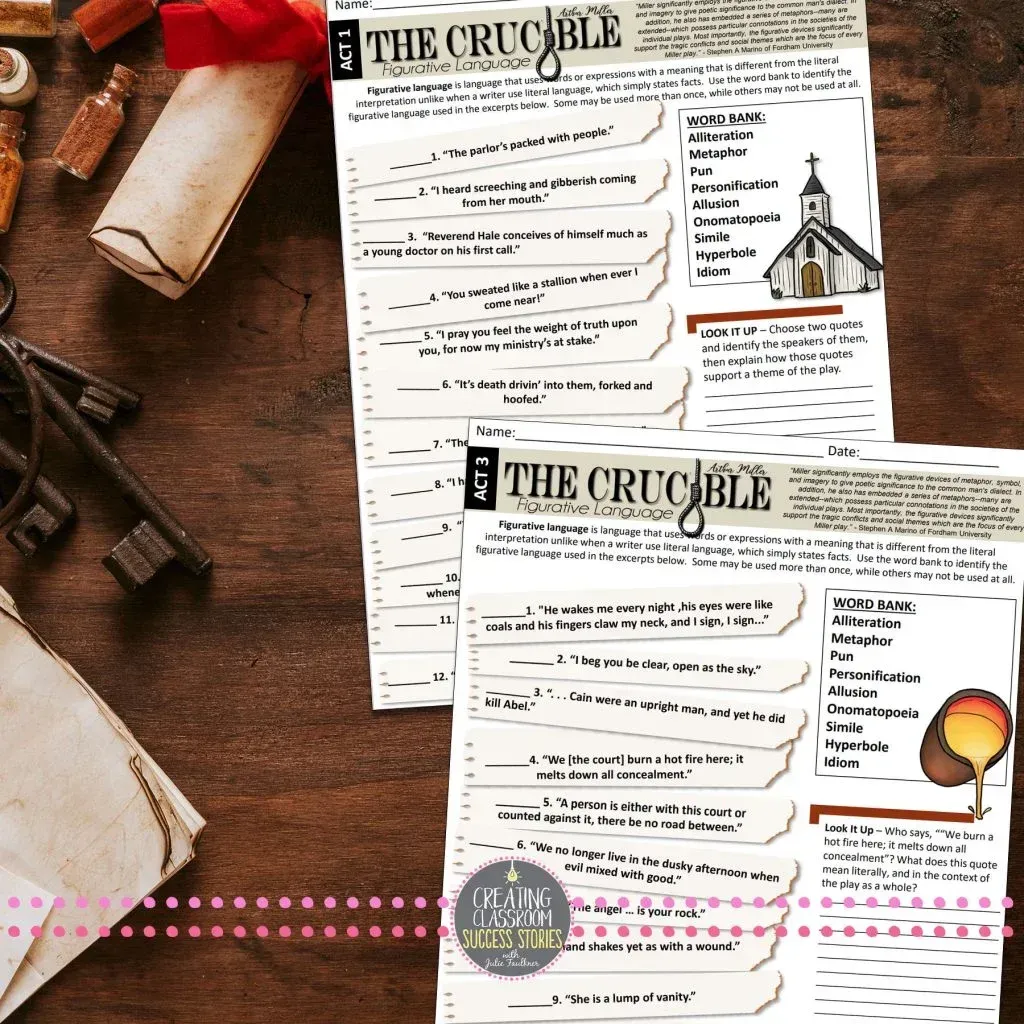

What It Is:

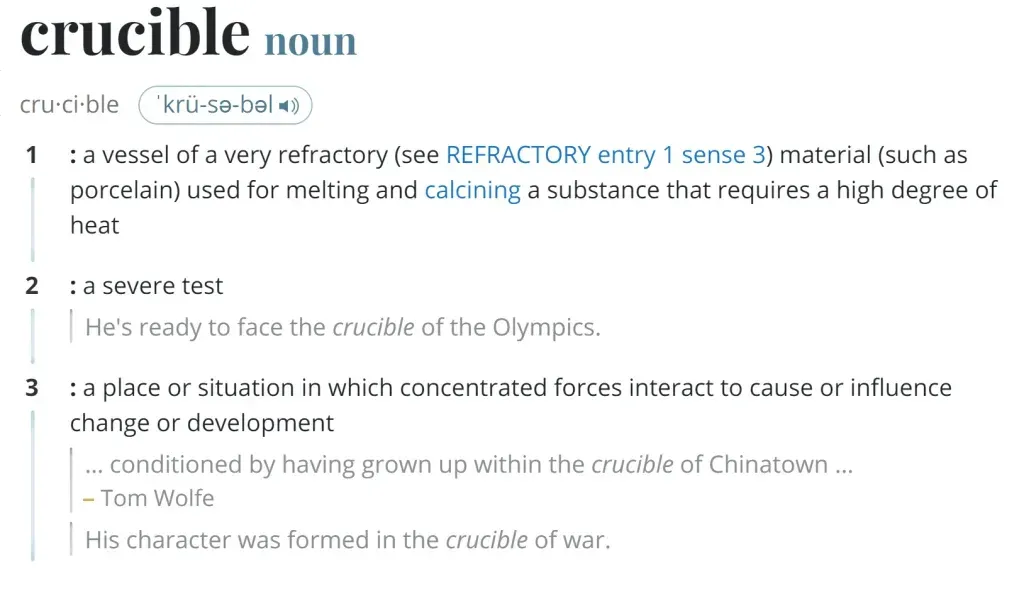

Figurative language shows up through dialogue throughout the play and in the title as well. To me, Miller’s use of language is what makes the play so interesting to read and act out – and quotable! There are so many passages where the words hold so much weight and beauty and mean so much because of the way Miller plays with the language. And, speaking of playing with the language, the title itself is a play on words. The word crucible has three different definitions:

Analyzing the meaning behind the language as well as the title is an important part of any literature-based unit plan.

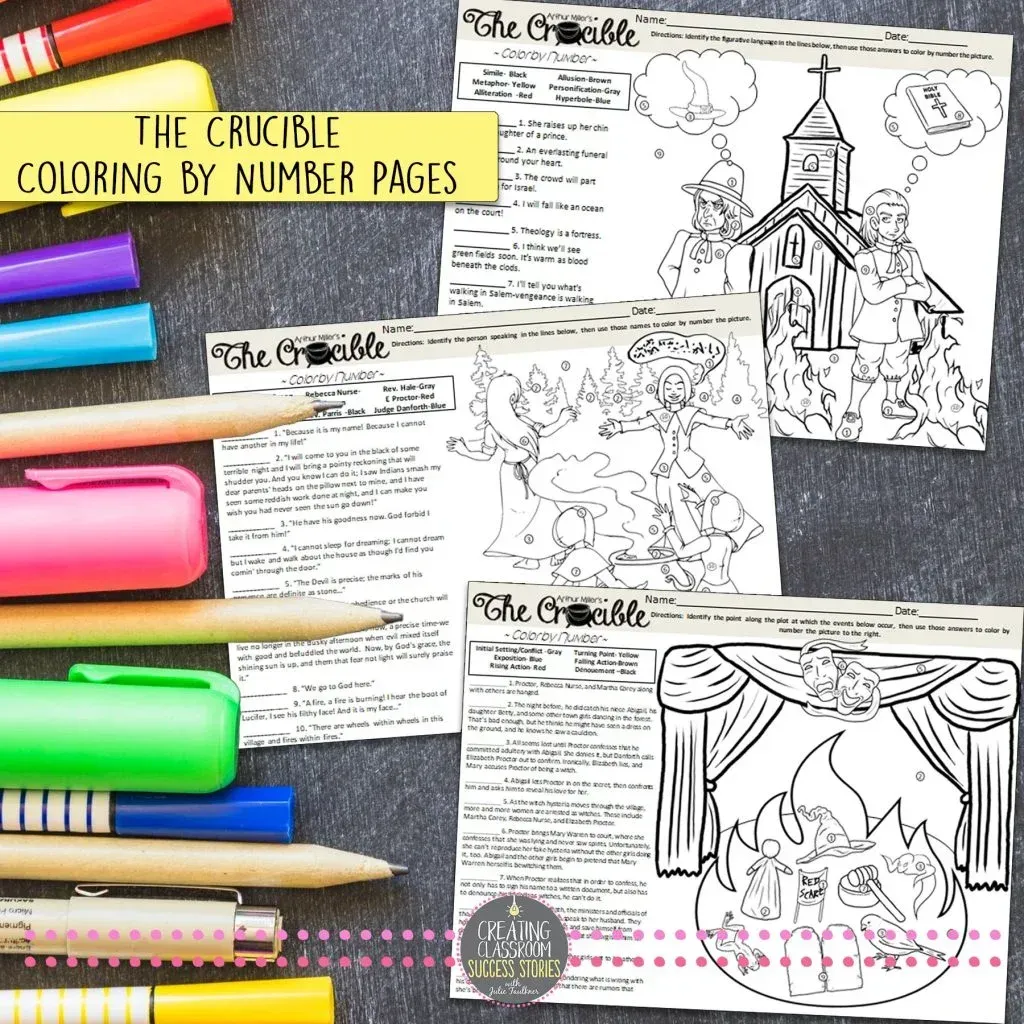

How I Teach It: A quick review of figurative language is always a good place to start. If you need a solid student-facing tutorial of the types, you can use my video with students. It’s free. Then, with each act, I have students complete a figurative language exercise where they not only identify but also explain lines from the play that include figurative language. I even made a figurative language page in my The Crucible coloring sheets. At the end of the play, one of the culminating writing prompts we do involve students explicating the meaning of the title, given all definitions. This prompt and my figurative language worksheets can be found in my The Crucible Unit Complete Literature Guide.

TEACHABLE MOMENT #4) THE ELEMENTS OF DRAMA

What It Is: The elements of drama are unique to the dramatic genre of literature. These terms include monologue, soliloquy, aside, stage directions, and dialogue.

How I Teach It: These terms are best taught as a vocabulary lesson at the beginning of the unit. By the time students are to the level of schooling where The Crucible is being read, they have been exposed to these terms before. I have learned, though, that it’s better to be safe than sorry — never assume. So you might be in one of two boats:

- If you are teaching The Crucible, in part, to cover the elements of drama and students are learning these terms for the first time, then you’ll want a more intensive lesson. I have an entire teaching pack prepared to teach and test the terms, and it’s not included in my The Crucible teaching pack.

- If you are just reviewing the terms, I like to go over the terms in context as a “step-back” or close reading exercise after we’ve read Act 1.

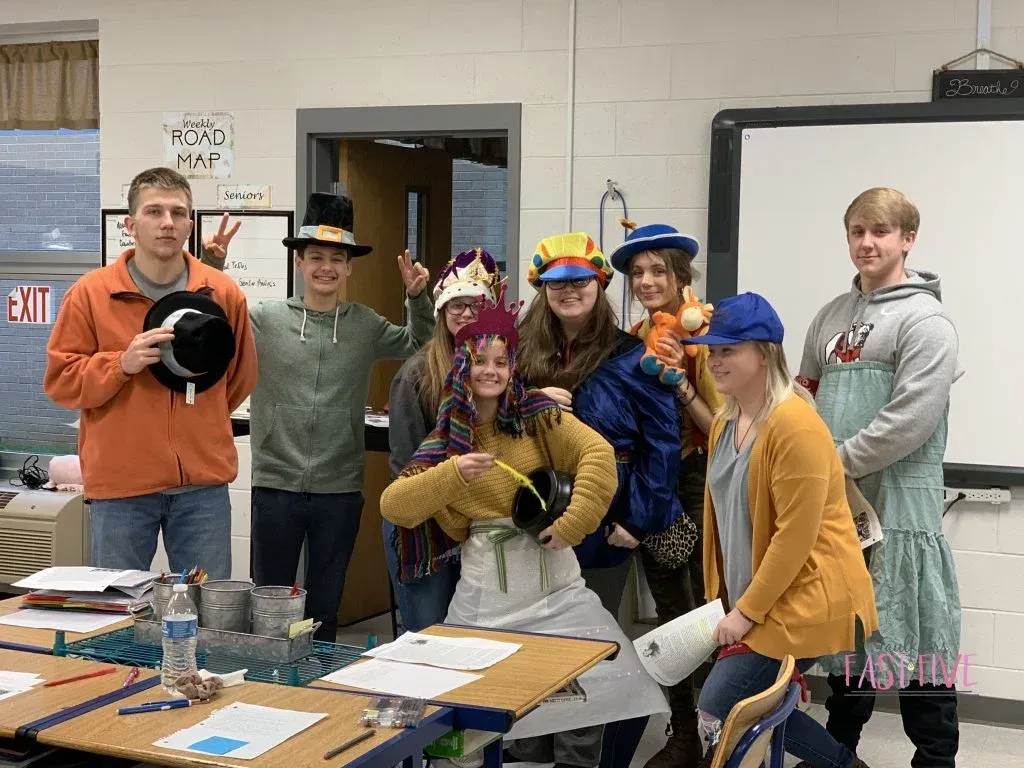

Along with this “must have” when teaching The Crucible, it is important to note that it is these elements that make it a play– and a play is meant to be seen and heard! Plan to grab some costumes and give students space to make the play come alive! My teaching pack includes abridged scripts for each act, which are perfect for reader’s theater.

Another note here regarding stage directions – I don’t read the long stage directions that Miller sprinkles in between and throughout the acts. We’ve done most of that in pre-reading, and I want to keep the momentum going. I use an audiobook from Amazon that we read along with while I instruct. I don’t have students read each word of the play; it takes too long and often isn’t always as enjoyable. I also do show a few clips of it being acted throughout as well as clips of the movie version. Listening, watching, reading excerpts aloud, and acting in reader’s theaters provide more variety.

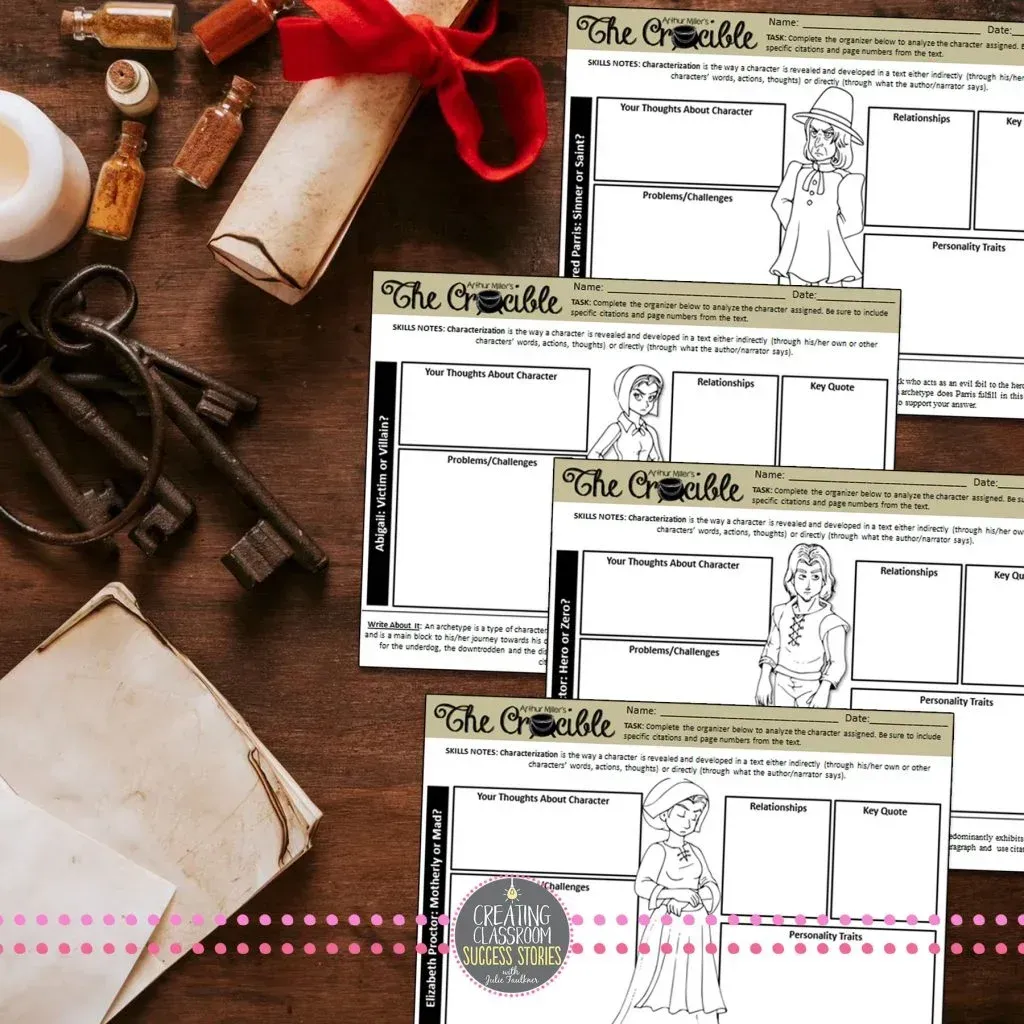

TEACHABLE MOMENT #5) CHARACTERIZATION

What Is It: Characterization is how a writer paints the “people” in the story, but in The Crucible, the motives of each character tie directly to the conflict and propel the plot.

How I Teach It: As stated above with the elements of drama, if your students are unfamiliar with the techniques of characterization, you’ll want to do a lesson with them at some point. Otherwise, you can just review. In my case, I usually review (at the junior level), and then we start working on our character motive trackers with each act. A lesson characterization is not included in my Crucible unit, but I do have a teaching pack available (see it here). Characterization activities are most certainly included in the unit, though.

Taking a deep dive into the “wheels within wheels and fires and within fires” of this play has always been something I look forward to in my high school English curriculum. In fact, teaching The Crucible in American Literature has always been one of my favorite texts for several reasons. It may seem that a play written decades ago about people from centuries ago might not appeal to today’s teenagers, but I never found that to be the case. Once we dove into the dialogue, my students were always hooked from the opening scene.

Love this content?

Sign up for my email newsletter with more tips, ideas, success stories, and freebies!