How to Host Successful

Classrooms Discussions

If your students are like mine, they are glued to their screens 99% of the time. What’s grabbing their attention? That would be apps that survive on trendy video clips, silly captions of selfies, or short chats with nonsensical abbreviations and emojis that are lost on me. What students really need is the ability to communicate in person effectively and fluently – and this much-needed skill can start in your classroom with an old-fashioned face-to-face discussion.

There are many methods, procedures, suggestions, tools, and ideas on how to best host a classroom discussion. Over the years, I’ve tried most of them, if not all of them. Some worked for certain groups of students and some didn’t. What I’ve learned through experimentation is that you really need quite a few tools in your toolbox, but also it is important to note that having the classroom discussion of your dreams takes time, practice, a clear understanding of the material, and a safe classroom culture.

In this blog post, I’m sharing five things it takes to host successful classroom discussions in your middle and high school English classrooms.

USE QUESTIONS AND/OR DISCUSSION STEMS

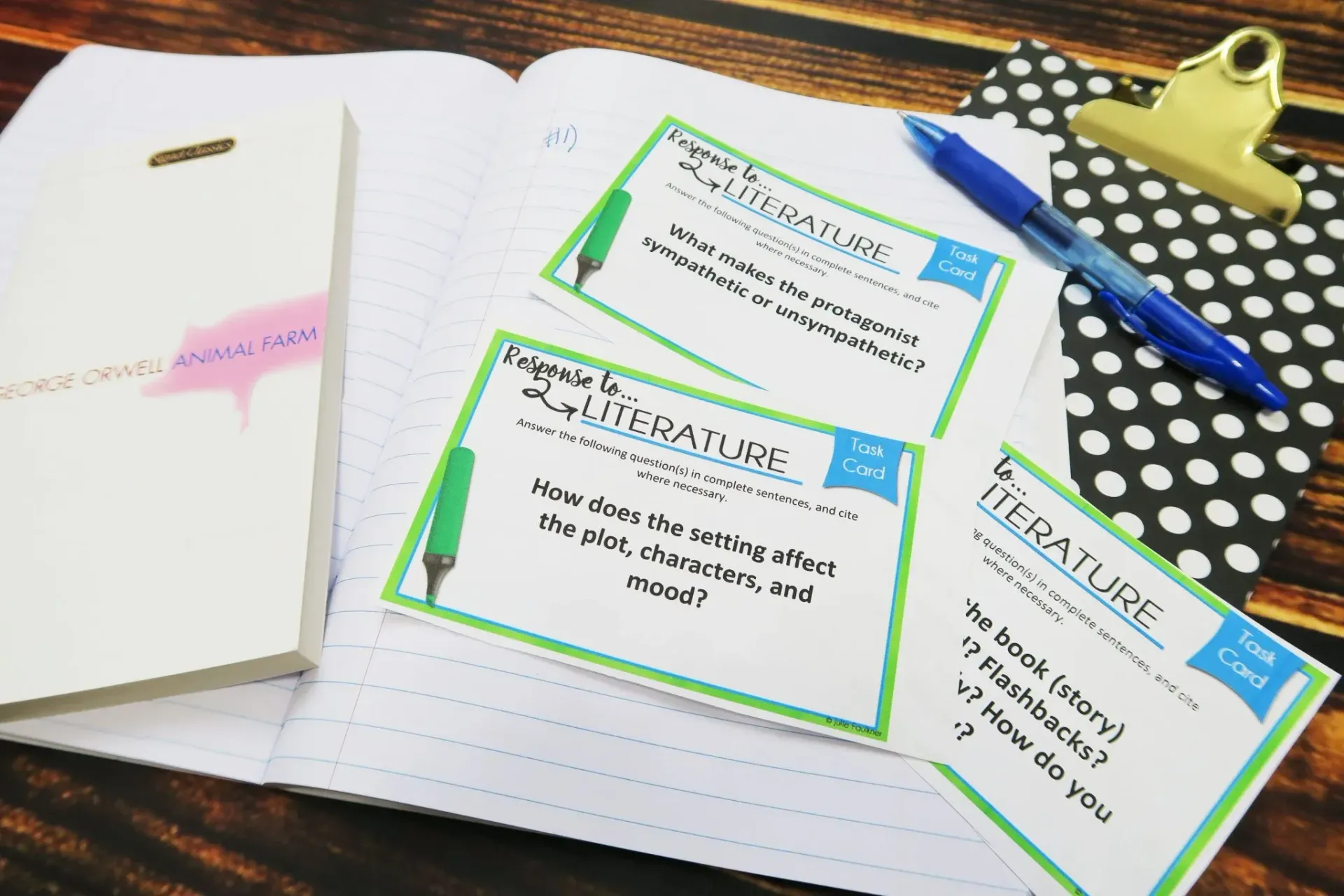

Teacher-prepared questions or student-prepared questions can work successfully depending on what level your students are at in the discussion process. I would suggest that if your students are new to discussions, use the teacher-prepared questions approach the first couple of times because that models the right type of questions that students need to be asking about a text to get the most out of the discussion. Using task cards with pre-written questions is a good option. Give each student one or two cards at first, so they aren’t overwhelmed. Build in some time for them to answer before you open to the group, and make yourself available to give feedback individually before the discussion starts. It would be the same process if students were writing their own questions. Having questions and answers prepared ahead of time puts students on the same playing field, so to speak, at least initially. Everybody comes to the discussion with something to say that he/she can feel confident about, and student confidence is a key ingredient in having a successful classroom discussion.

Tools for useful and engaging questions/stems:

- Literary Analysis Task Cards, Digital and Traditional BUNDLE

- Emoji Puppets with Stems for Discussions, Review, and Reflection

- Accountable Talk: Productive Discussions & Communication Pack

- Literature Analysis Worksheets, Printable and Digital

Watch my students use the Emoji Puppet Stems in this video:

Another strategy I like to use to prompt comment preparedness is the 3-2-1 strategy. I explain it in this video:

LET THE STUDENTS LEAD CLASSROOM DISCUSSIONS

It is not always easy to step back as the teacher and wait for students to speak up. We are trained to think that we have to do all the talking or that silence equals a lack of understanding. In some cases, the latter may be true, but most of the time with classroom discussions, students need a minute to formulate an answer before they speak up in front of their peers. Letting the students lead also builds their confidence over time, and they learn how to encourage each other as well. An article on Edutopia entitled “Extending the Silence” suggests at least 15-20 seconds of wait time especially when students don’t know the answer. The article states, “Not every learner processes thinking at the same speed. Quality should be measured in the content of the answer, not the speediness,” and I wholeheartedly agree. The level of critical thinking and problem-solving required to participate in a meaningful conversation about a text is arguably one of the highest that students might encounter, especially when they know they are going to be required to keep it going. I would suggest only speaking up when you can see that the productive struggle has just become more of a struggle: if the silence goes on for minutes, if there is nothing left to say, if comments begin to repeat, or if the tone shifts. Otherwise, sit back and enjoy your students’ perspectives!

HOLD STUDENTS ACCOUNTABLE TO THE TEXT IN DISCUSSIONS

I always tell my students that there is a ton of flexibility when it comes to literature. That means that most of the time their interpretations are acceptable when they can be backed up with line support. However, I do tell them that there are wrong answers. So, when they get out in the weeds or just have a blatantly erroneous reading of a text due to too much speculation, misreading, failure to remember details correctly, etc., we have to stop and go back to the text. Sometimes they will check each other, and other times I need to step in and ask students to take another look at the text. It is necessary to establish text dependency with all classroom discussions about literature from the start. We may reread the passages being discussed. Other times I might ask for line support. When students are writing answers to their questions from the task cards, for example, always require textual evidence. Otherwise, the purpose can get skewed, and the ultimate purpose of a classroom discussion is two-fold: teach students to correctly analyze a text and effectively communicate those ideas to others.

Also, when thinking about accountability, grading comes to mind, and grading can be a sticky topic when it comes to discussions. I want my classroom discussions to be organic and free from judgment. I am usually enjoying the moment so much that I don’t like to take notes or make marks on who talked or didn’t. I’ve done that in the past, and I know it works well for some classrooms. I’d rather give a reading quiz or a prompt where students write afterward. Other times, students have done work prior to the discussion to prepare, and I’ll collect that. These days, I’m more in the space where I want to experience the discussion rather than evaluate it from the outside looking in. Plus, I want students to see the value of the discussion beyond the letter grade.

PHYSICAL POSITIONING IN CLASSROOM DISCUSSIONS MATTERS

For this one, I’m taking a page from one of my favorite professional development authors/speakers. Dave Burgess, author of Teach Like a Pirate, suggests, “In order for all members of the classroom to be engaged and learning, both the teacher and the students need to be immersed in their instruction/learning.” Switching up your seating arrangement to a circle where everyone is facing each other sets the stage for better communication practices. Plus, it is something out of the norm and builds excitement. This simple transformation according to Burgess “provides an uncommon experience for your students and they will reward you with an uncommon effort and attitude.” I want that as a teacher, and I know my students want that, too.

TROUBLESHOOTING PROBLEMS IN CLASSROOM DISCUSSIONS

Over-eager students and reluctant students will likely be your biggest issues with classroom discussions. I don’t like to force students to speak up, and honestly, sometimes I rely on my more outspoken students at times. In some cases, the more quiet students need to see the process modeled for them. They have their questions and answers prepared, but they aren’t comfortable with their own voice. I just give them time and small pushes in the right direction. For your eager students, validate their enthusiasm and gently remind them that you’d like as many voices as possible to be heard. Ask the students who’ve had quite a bit of “airtime” during the discussion to “stick a pin” in their remaining ideas, so that we can come back to them if no one else covers them. That typically doesn’t cause them to shut down, and it reminds other students they need to speak up!

Avoiding a question/answer session is another issue to watch out for when conducting classroom discussions. This happens a lot of times when students are new at discussions or if students know a quiz will follow. In the latter situation, students are just phishing for what the teacher is looking for and/or guessing what will be on the quiz rather than truly discussing the passage. There’s nothing wrong with giving a quiz after a discussion, but students need to know that the purpose of the discussion isn’t to “review” the material on a basic level. In other cases, it just goes back to pausing and letting the students lead, holding back, and resisting the urge to answer every question that is posed.

The benefits of classroom discussion abound. Students can make text-to-text connections, text-to-self connections, and even text-to-world connections. Check out a few other posts I have regarding my book club procedures: I Don’t Do Literature Circles and Setting Up a Classroom Book Club.

Watch/Listen to a version of this post here (on TPT) and here (on IG).

Love this content?

Sign up for my email newsletter with more tips, ideas, success stories, and freebies!