Formula for Classroom Success Series

Post #4 How to Make Struggle Productive

I’m back today with the next post in my classroom success series. Today’s topic is the struggle- and we all know the struggle is real. However, many times the struggle does not always result in a deeper understanding of the essential learning standard or an “ah-ha” moment. Sometimes, the struggle results in frustration, lack of confidence, lack of willingness to stay engaged, behavior problems, or worse, complete shut down for the rest of the day. I’m a believer – cue THE MONKEES here – in the struggle because I know how valuable it can be. But there are a few behind-the-scenes tips and tricks that you need to know in order to have a successful classroom experience. Here’s what I’ve found to work for me over the years – aka How to Make Struggle Productive.

1. Have a reason for the struggle

I find that most frustration that students experience bubbles up when they do not see or understand the goal or purpose up front. I like to set up my lessons with an essential question, or I provide a brief outline of the lesson at the beginning, so students know what they are trying to accomplish. Only rarely do I give students something brand new and turn them loose. I’ve tried that, and it’s never been successful. (You can see a previous post in this series on the I do, We do, You do strategy.) Another way to ensure students know there is light at the end of the tunnel is to provide them with a detailed rubric up front. The feeling of accomplishment once students have persevered is immensely gratifying, but I also think providing something for positive reinforcement at the end builds motivation to keep trying. My rubrics usually consist of line items with a certain number of points for each item. Within that framework, I can allow partial credit for the different requirements. Pictured below is the one I use for short research projects, and it allows me to give three different grades on the project. Separating the rubrics out by categories also allows me to offer revision opportunities in one area at a time or instead of another. For example, my essay rubrics are similar to these, but the grammar is broken out. That’s so students can revise the content, but not the grammar. Because, as you may know, most times students just go in to edit – not revise – the paper hoping for a few more points for correcting a spelling or comma mistake here and there. If that’s not my goal, this type of rubric sets my grading up in a way that helps students see the different parts and that all the parts are significant and separate.

2. Teach growth mindset &create community where mistakes are seen as pathways to discovery not failure

I like the following graphic to explain the difference between fixed mindset and growth mindset. Students need to know that a classroom is a place where learning is a process. So, how to do that? Working with honors students, particularly, I’ve seen that they want to have a perfect score right out of the gate – even on new material. Or, they don’t want to approach new material because it may not result in that 100 in the grade book. One way to try to instill the idea that learning is a process and to learn from criticism is to offer a revision policy. My revision policy is not a “Here, redo this for a better grade; take this same test again; let me go over the answers so you can write them down and turn them in” type policy. It’s a “nitty-gritty; you have to work for it” type policy. I’ve done this several ways in my high school English classroom. Sometimes I’ve allowed students to revise one essay from the year – content only. Other times I’ve noticed that an entire class needs work in a certain area, so we workshop that and then they revise. The fixed mindset usually rares its ugly head when students are forced to revise, but if scaffolding and a clear purpose, they begin to embrace the challenge and see its benefits.

3. Scaffold with checkpoints

Some students come into class ready for a challenge and know how to pace themselves along the way. Other students, for various reasons, try to swallow the elephant all at once. Honestly, I tend to be that person who gets anxiety looking at a big project because I try to tackle it all at once. To help students to learn how to take it one step at a time chunk sections of the task, provide mini-deadlines, or offer checkpoints. I usually start the year scaffolding larger tasks for students until it becomes more ingrained, and they learn to do it on their own. My yearbook class comes to mind specifically when I think about giving them time and space – well, really my yearbook class comes to mind with all of these. But making 192-page book in six months from scratch can be very overwhelming and frightening. We take it step by step, a page a time until they figure it out.

4. Give them time, space, and choices

To allow students the full experience of the productive struggle, sometimes teachers have to hold back. We don’t want to see

students fail, so we feel the need to swoop in and “help” before letting them try on their own. In my classroom, I tell students that I love “awkward silence.” It’s kind of a funny way to let them know that I am going to wait on them to answer without bailing them out, but it takes the awkwardness away because I dispelled it up front. In yearbook class, for example, it would be very easy to do quite a bit of hand-holding or rescuing because the outcome is so high stakes and time is extremely limited. But I hold back as much as I can when I know it’s something they really can accomplish on their own: writing a caption or headline, uploading photos, or creating a photo presentation. It’s just a matter of knowing your students’ knowledge set and where you know they can go. The amount of space or time that is logistically built into the schedule for completing the task is another component. If we want students to work through the process and do a great job, they need time to plan, think, practice, create, proof, and finalize. Sometimes that could take days! I also like to offer students choices when we are going into a project or task they will be working through on their own. Choices can come in the form of a menu board with different project options; three different stories from which to choose when constructing a literary analysis; or simply allowing students to choose their own research topics. There’s something psychological about making a choice, and it’s a strategy I’ve found that really works to get buy-in. The menu board pictured below is from my

Columbine unit (coming Summer 2016) and allows students to choose their own project, topic, and grade. Most of the time, I use this type of assignment as the culminating task.

5. Know when it’s not productive and shut it down

There are a few times when students just aren’t going to be able to get there alone, and that can be for a couple of reasons. Once I assigned a cause and effect writing prompt, and my juniors worked the entire period, and even the best student only had a couple of paragraphs done. Others had not been able to grasp the concept well enough to write on the actual topic. The rest just really didn’t have anything. At the end, they were frustrated and really confused about what I had wanted. I stepped back and realized that prompt was faulty. I didn’t need to give them more time the next day to experience the struggle. I apologized, we brainstormed a better prompt together, and their new essays turned out much better the second time around. Other it may be that the students just need a little more direction, guidance, or time. I want the struggle to be real, but only when it’s really worth it. I liked this video from the Teaching Channel by Carol Jago about productive struggle. Keep calm and risk productive struggle for amazingly successfully classroom results! Get the cute poster below in my Back to School Survival Kit for any subject 7-12!

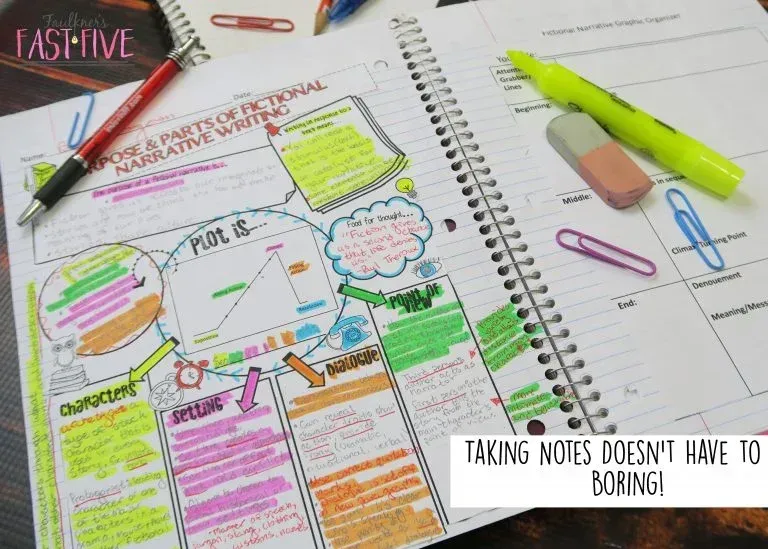

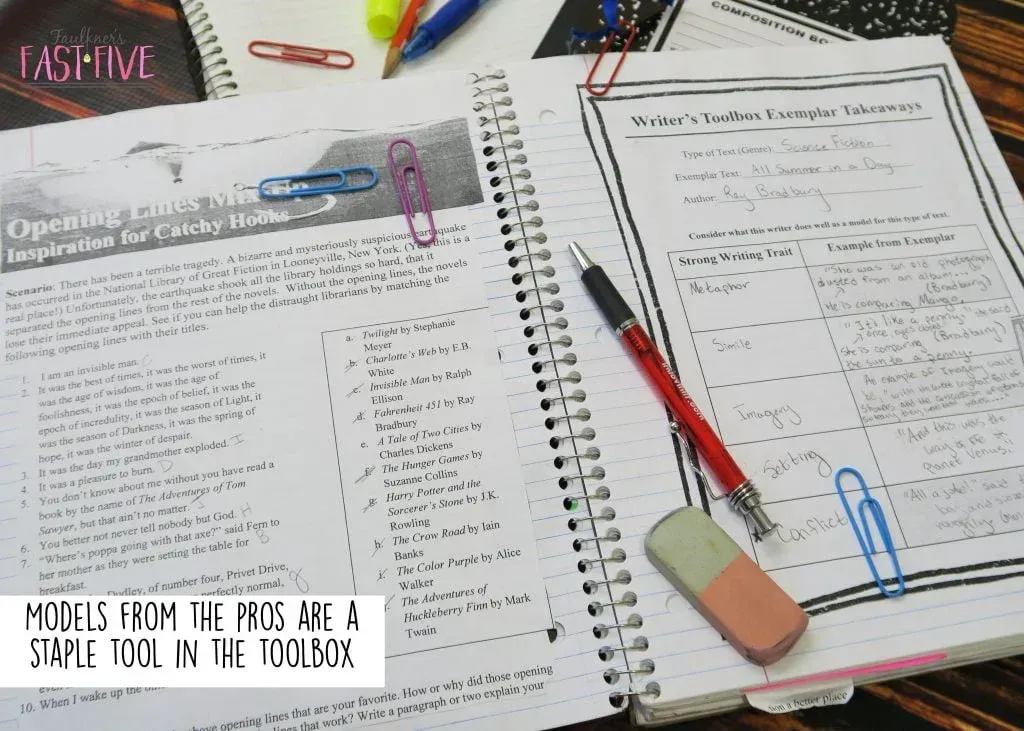

How will this help my students be better writers?

Writing is a process, and part of that process is learning the pieces and parts and seeing how we grow and change. Facing challenges and celebrating triumphs gives students the confidence they need to keep writing. I also think seeing everything in one place gives them a sense of accomplishment because it’s something they created. It’s certainly only one piece of the puzzle, but it’s the piece that holds it all together. The writer’s portfolio becomes the literal toolbox for students with everything they need to pick up and get started building their essays.

What do I need to get started?

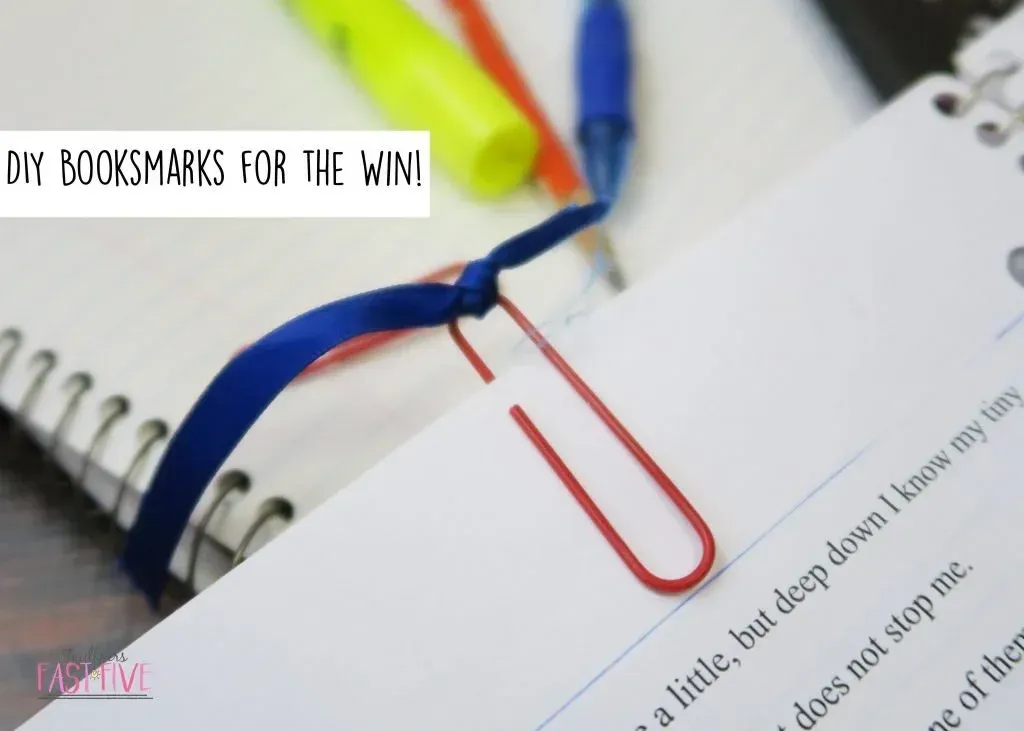

Plan to provide or require your students to have a simple one-subject spiral notebook. It’s as simple as that! No fancy binders, sheet protectors, etc. Just a simple $.50 notebook. You’ll also need some large paper clips and ribbon to make bookmarks. Students mark the page of where I need to flip to grade their current writing piece, and it saves so much time and eliminates the page flipping! Of course, scissors and stick glue will be required as well!

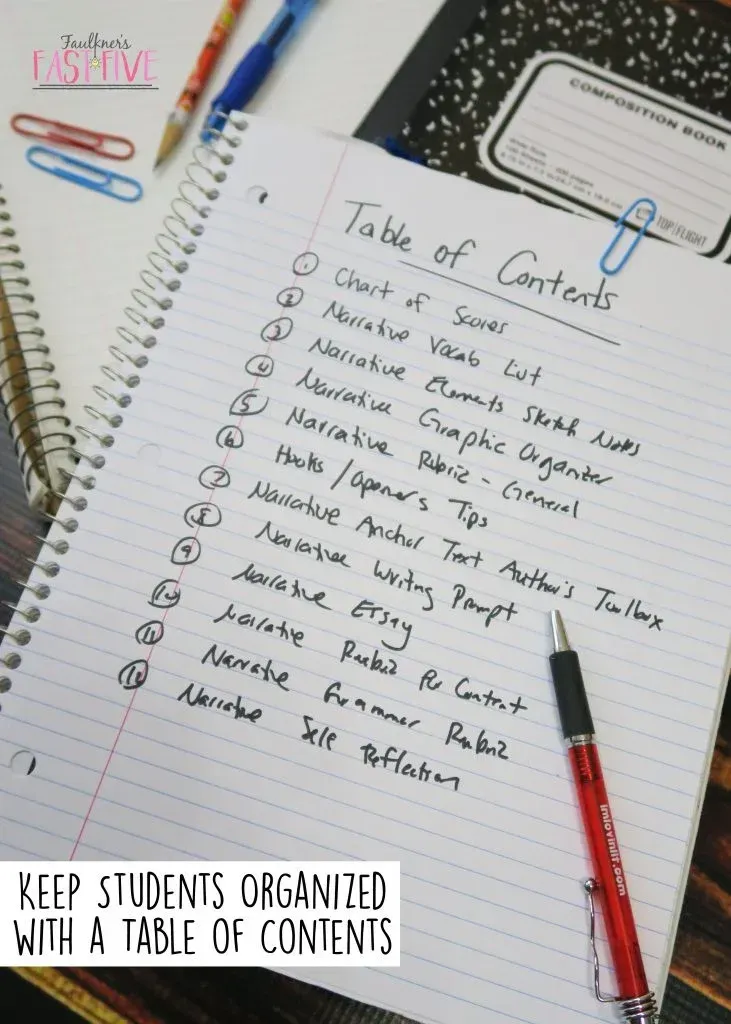

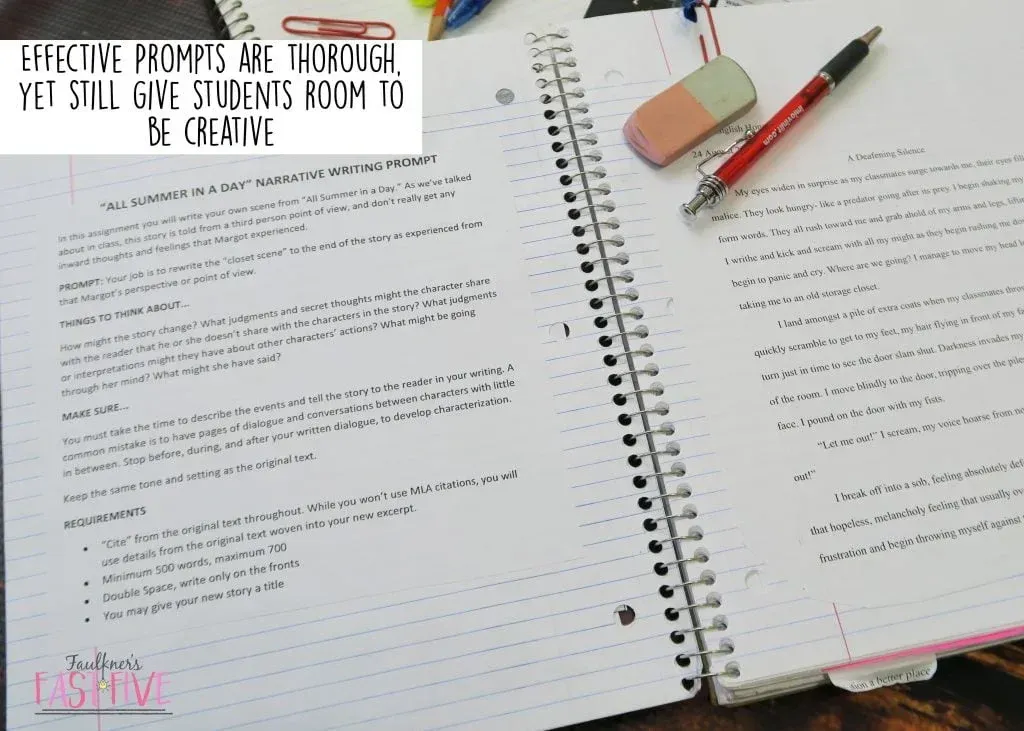

What goes in the writer’s notebook?

Everything. Again, very simple! Everything related to writing. I do like to have my students arrange the notebook by the units we do, which are by the modes. Typically, the first unit is the narrative mode.

Why not just have it all in the regular binder they use for the class?

While writing isn’t a separate part of the class, I think the writer’s notebook does need to be, so when students need to begin writing, their space isn’t cluttered. Disorganization can be a stumbling block for writers, and we want to create an environment as free from distractions as possible. Virginia Woolf said to be a successful writer, she needed “a room of her own.” This writer’s portfolio is a space set aside for students to be adventurous, to make mistakes, to try new things, to have successes, to brainstorm, and to create. It is a “room of [their] own” to be successful student writers.

Sign up for my monthly newsletter – “Teaching Tidbits” – that is delivered directly to your email inbox each month. Each month you’ll get announcements, tips for teaching, updates on new and revised resources, and, of course, an email-only exclusive FREEBIE! (You can SUBSCRIBE on the "Stay Connected" Tab!)

Love this content?

Sign up for my email newsletter with more tips, ideas, success stories, and freebies!